Umbra

Aus Freiheit statt Angst!

Backgrounder

Summary

- Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention is the most privacy invasive instrument and the least popular surveillance measure ever adopted by the EU. The Data Retention Directive mandates the indiscriminate collection of sensitive information about social contacts (including business contacts), movements and the private lives (e.g. contacts with physicians, lawyers, workers councils, psychologists, helplines, etc) of 500 million Europeans that are not supicious of any wrongdoing. According to one poll, 69.3% of citizens opposed data retention, making it the most strongly rejected surveillance scheme of all, including biometric passports, access to bank data, remote computer searches or PNR retention.

- Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven harmful to many sectors of society. It disrupts confidential communications in areas that legitimately require non-traceability (e.g. contacts with psychotherapists, physicians, lawyers, workers councils, marriage counsellors, drug abuse counsellors, helplines), thus endangering the physical and mental health of people in need of help as well as of people around them. The inability of journalists to electronically receive information through untraceable channels compromises the freedom of the press, which damages preconditions of our open and democratic society. Blanket data retention creates risks of abuse and loss of confidential information relating to our contacts, movements and interests. Communications data are particularly susceptible to producing unjustified suspicions and subjecting innocent citizens to criminal investigation.

- Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven superfluous and counter-productive for removing market distorsions. By requiring all EU Member States to enact blanket retention legislation, the EU Data Retention Directive has resulted in a far larger patchwork of national blanket retention legislation than would have existed without the Directive. There are several alternative options to prevent market distortions without mandating blanket data retention throughout the EU (e.g. by prohibiting national data retention legislation or by making full cost reimbursement compulsory where national data retention legislation exists).

- Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven superfluous for the detection, investigation and prosecution of serious crime. Although retained communications data is occasionally useful for those purposes, there is no evidence that such benefits depend specifically on blanket data retention legislation. On the contrary, crime statistics reveal that there is not a single EU Member State where blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has had a statistically significant impact on crime or crime clearance. Crime statistics prove that several states in and beyond Europe (e.g. Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Romania, Sweden, Canada) prosecute crime just as effectively by using targeted instruments, such as recording data that is needed for a specific criminal investigation only (“data preservation”).

- Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven to violate fundamental rights and unable to stand its ground against court challenges. In view of the scale of damage done to fundamental rights by data retention and the lack of evidence for a statistically significant impact on crime or the prosecution of crime, the concept of indiscriminately collecting information on the daily communications of every single citizen has been ruled disproportionate and incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. The EU Court of Justice is expected to annul the Data Retention Directive in 2012 for violating the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, having regard to the fact that alternative measures are available which are consistent with the Directive's legal objective of "safeguarding the proper functioning of the internal market" while at the same time causing far less interference with innocent citizens' right to respect for their private life.

- The EU must no longer force blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention on its Member States but prohibit such laws in favour of expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data that is needed for a specific investigation. The EU Commission should propose outlawing national data retention legislation in favour of a targeted and proportionate system as agreed in the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime, thus targeting suspects of serious crime instead of placing all 500 million EU citizens under general suspicion. For as long as the EU Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights have not yet ruled on pending complaints against data retention legislation, the Commission must not fine or threaten to fine Member States that refuse to (re)enact such legislation in order to uphold their citizen's fundamental rights and freedoms.

Introduction

The EU Commission has recently published a report evaluating the controversial Data Retention Directive 2006/24/EC, which is to be revised later this year.

The EU Data Retention Directive 2006/24 requires telecommunications companies to store data about all of their customers' communications. Although ostensibly to reduce barriers to the single market, the Directive was proposed as a measure aimed at facilitating criminal investigations. The Directive creates a process for recording details of who communicated with whom via various electronic communications systems. In the case of mobile phone calls and SMS messages, the respective location of the users is also recorded. In combination with other data, Internet usage is also to be made traceable.

In 2010, the average European had his traffic and location data logged in a telecommunications database once every six minutes. According to official Danish statistics, every citizen is logged 225 times a day.[1]

According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), telecommunications traffic data reveals the identity of the colleagues, acquaintances and friends of a person in 90% of all cases. It can even be used to predict whether two people will meet within the next 12 hours in 90% of all cases. Traffic data generated by a person during a one month period will allow to predict where the person will be in the next 12 hours in 95% of all cases. Finally, traffic data can be used to predict a person's activities during the next 12 hours in 80% of all cases.[2]

The blanket and indiscriminate bulk recording of such telecommunications information on all 500 mio. EU citizens is, according to the European Data Protection Supervisor, "the most privacy invasive instrument ever adopted by the EU".[3] It is also possibly the most highly controversial EU surveillance instrument and is subject to protests throughout the EU.

A poll of 2,176 Germans found in 2009 that 69.3% oppose data retention, making it the most strongly rejected surveillance scheme of all, including biometric passports, access to bank data, remote computer searches or PNR retention.[4] A 2008 Eurobarometer poll found that a large majority of 69-81% of EU citizens rejected the idea of "monitoring" the Internet use or phone calls of non-suspects even in light of the fight against international terrorism.[5]

We welcome the legislator's intention to have the "data retention experiment" and its impact evaluated. The European Data Protection Supervisor called the current evaluation "the moment of truth" for the "notorious" directive. Unfortunately the Commission's evaluation methods have turned out to be fundamentally flawed. Rather than procuring an independent assessment that satisfies scientific standards, the Commission has produced a political document. This is why we have decided to provide important background information and facts in this report that have been ommitted in the official evaluation report.

Impact on citizens and professionals

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven harmful to many sectors of society.

The Commission argues that the Directive protects (or should protect) personal data and fundamental rights by setting standards concerning purpose limitation, retention periods and procedures for access to retained data. It is true that the Directive were a data protection instrument if it set limits on pre-existing national retention schemes and imposed safeguards only. In actual fact, however, the Directive allows Member States to go beyond its limits in most respects (e.g. types of data to be retained, purpose of retention) and does not address access to retained data at all.[6] Most importantly, in imposing a blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention scheme on all Member States, the Directive does the opposite of protecting data from being processed without consent. If the purpose of the Directive truly were to protect human rights, it would ban national data retention laws or impose limits on pre-existing laws rather than itself mandating such blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention.

With a blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention regime in place, sensitive information about social contacts (including business contacts), movements and the private lives (e.g. contacts with physicians, lawyers, workers councils, psychologists, helplines, etc) of 500 million Europeans is collected in the absence of any suspicion. Telecommunications data retention undermines professional confidentiality, creating the permanent risk of data losses and data abuses and deters citizens from making confidential communications via electronic communication networks. Blanket retention has a major impact on consumers in that they can no longer use telecommunications in situations that legitimately require non-traceability.

- A poll[7] of 1,000 Germans found in 2008 that indiscriminate bulk data retention is acting as a serious deterrent to the use of telephones, mobile phones, e-mail and Internet. The survey conducted by research institute Forsa found that with communications data retention in place, one in two Germans would refrain from contacting a marriage counsellor, a psychotherapist or a drug abuse counsellor by telephone, mobile phone or e-mail if they needed their help. One in thirteen people said they had already refrained from using telephone, mobile phone or e-mail at least once because of data retention, which extrapolates to 6.5 mio. Germans in total. There can be no doubt that obstructing confidential access to help facilities poses a danger to the physical and mental health of people in need as well as of the people around them.

- The German Working Group on Data Retention has received ample reports on negative effects of data retention, which have been summarised in its response to the Commission's evaluation questionnaire.[8] The indiscriminate retention of all communications data turned out to disrupt confidential communications in many areas, affecting victims of sexual abuse, political activists, journalists, accountants, lawyers, businessmen, psychotherapists, drugs advisers and crisis line operators.

Citizens who refuse to use retracable communications channels act rationally as there have been concrete examples of abuse of communications data:

- In 2006, 17 million sets of mobile phone subscriber data were sold by employees of T-Mobile, among them secret telephone numbers of ministers, politicians, former German heads of state, economic leaders, billionaires and church officials.

- In Ireland, a female detective sergeant in the Irish police's intelligence division is being investigated over claims that she used her position to check her former lover's phone records.[9] In Germany an intelligence officer was alleged in 2007 to have used his powers to spy on his wive's lover.[10]

Although these abuse cases cannot always be directly linked to the data retention directive, it is clear that the directive removes the only truly effective way to prevent such data abuse by not storing the sensitive data in the first place.

More wide-spread than cases of abuse are cases of communications data leading to falsely suspect an innocent person of an offence not committed by them or not committed at all. Communications data are particularly prone to such errors as it is easy to make mistakes in the process of identifying a subscriber (e.g. transposed digits, mismatching time zones) and because communications data relate to an account only which can have been used by anyone (e.g. public wifi hotspot). Communications data have again and again lead to innocent citizens being put under surveillance, having their houses searched, being arrested or being publicly accused of abhorrent offences. Also location data is often used to investigate a large number of law-abiding citizens simply for having been close to a scene of crime.

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention undermines the protection of journalistic sources and thus compromises the freedom of the press. Overall it damages preconditions of our open and democratic society.

- In a poll of 1,489 German journalists commissioned in 2008, one in fourteen journalists reported that the awareness of all communications data being retained had at least once had a negative effect on contacts with their sources.[11] The inability to electronically receive information through untraceable channels with blanket data retention in place affects not only the press, but all watchdogs including government authorities.

- German telecommunications giant Deutsche Telekom illegally used telecommunications traffic and location data to spy on about 60 individuals including critical journalists, managers and union leaders in order to try to find leaks. The company used its own data pool as well as that of a domestic competitor and of a foreign company.[12]

- In Poland retained telecommunications traffic and subscriber data was used in 2005-2007 by two major intelligence agencies to illegally disclose journalistic sources without any judicial control.[13]

- In the Netherlands, retained data was used to reveal anonymous sources of a journalist that had nothing to do with the investigation. Also telecommunications data of non-suspects were accessed merely they had the same first name as the suspect.[14]

The Article 29 Group has stressed that risks of breaches of confidentiality are inherent in the storage of any traffic data. Only erased data is safe data. That is why the ePrivacy directive 2002/58/EC established the principle that traffic data must be deleted as soon as no longer needed for the purpose of the transmission of a communication.

Harmonisation

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven superfluous and counter-productive for removing market distorsions.

The data retention directive is based on article 114 (1) TFEU which allows the EU to approximate national laws "with the aim of establishing or ensuring the functioning of the internal market". The EU argues that differing national data retention requirements "may involve substantial investment and operating costs" for service providers[15], "may constitute obstacles to the free movement of electronic communications services" and "give rise to distortions in competition between undertakings operating on the electronic communications market".[16]

When the data retention directive was adopted in 2005/2006, only 5 of the then 25 Member States required communications service providers to retain certain communications data without cause, typically requiring the retention of less data for shorter periods of time than the Directive does. Another 5 Member States had legislation in place that would have allowed them to impose data retention requirements in the future.[17] 15 of the then 25 Member States had not enacted any data retention legislation.[18]

Today, the Directive being in force, 21 of 27 Member States are requiring service providers to retain communications data without cause[19] with national obligations varying widely as to

- the categories of service providers affected (the Directive imposes minimum requirements only),[20]

- the types of communications data to be retained (the Directive imposes minimum requirements only),

- the retention period for each type of data (the Directive imposes a period of 6-24 months for certain types of data and certain purposes, otherwise not harmonised by the Directive),

- the data safety requirements (not harmonised by the Directive),

- the purposes for which retained data can be used (the Directive imposes minimum requirements only),

- the conditions and procedure for access to and use of the data (not harmonised by the Directive),

- the reimbursement of costs (not harmonised by the Directive).

It is apparent from these facts that by requiring all Member States to enact blanket retention legislation, the Directive has ensued much higher "investment and operating costs" for service providers in the EU than they would have been faced with without the Directive, and has resulted in a far larger patchwork of national blanket retention legislation than would have existed without the Directive. The Directive thus itself constitutes an "obstacle to the free movement of electronic communications services" and "gives rise to distortions in competition between undertakings operating on the electronic communications market".

From an internal market perspective, several options exist to really remove "obstacles to the internal market for electronic communications" without imposing the concept of blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention on all Member States and citizens:

- The EU could prohibit national legislation mandating blanket data retention without cause in favour of a system of expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data as agreed in the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime.

- The EU could require Member States with (optional) national retention legislation in place to fully compensate the providers affected.

- The EU could require Member States without (optional) national retention legislation in place to impose a levy on their communications service providers, thus eliminating any competitive advantage they might have as a result of not having to retain data indiscriminately.

- The EU could amend the Directive so as to impose limits on (optional) national retention legislation only, rather than impose the concept of blanket communications data on all Member States, and still create a more harmonised market than exists at present. For example, a blanket retention period of 0 to 3 months would create a far more harmonised situation than imposing a retention period of 6-24 months.

When proposing the data retention directive, the Commission itself considered compulsory compensation the key element to prevent market distortions: "The cost reimbursement principle will allow creating a level playing field for the electronic communication providers in the internal market."[21] When the Directive was adopted, however, the one element that would have contributed to creating a more level playing field - cost reimbursement - was removed from the Directive. Yet this element is a simple and far less invasive way of preventing market distortions than trying - and failing - to establish a harmonised data retention scheme throughout the EU.

Interestingly, the Commission is now citing a study according to which the retention costs of an ISP with half a million subscribers is around 0.75 Euro per subscriber in the first year and 0.24 Euro in subsequent years, with data retrieval costs of about 0.70 Euro per subscriber and year. If blanket retention requirements have "no significant impact" on competition or investment, there is no justification for the EU to harmonise such national legislation at all. The European Court of Justice has repeatedly held that the EU may rely on article 114 TFEU with a view to "eliminating appreciable distortions of competition" only.[22] If national data retention requirements result in costs of no more than 1 or 2 Euros per customer and year, they cannot seriously be claimed to appreciably distort cross-border competition.

Besides we remain unconvinced by the EU Court of Justice's decision that national legislation mandating the retention of data for law enforcement purposes "have as their object the establishment and functioning of the internal market" within the meaning of Article 114 TFEU. If the Court's reasoning was correct, the EU would be competent to harmonise all national information keeping or other requirements imposed on companies for purposes such as law enforcement, taxation, national defense and educational purposes. For example the EU could harmonise tax record keeping requirements or national standards for manufacturing police weapons, military equipment or school textbooks, all in the name of internal market harmonisation. This by far exceeds the scope of article 114 TFEU.[23]

In conclusion, the Directive has not only failed its purpose of creating a more level playing field for service providers but has proven to be counter-productive in this respect, creating a far more patchworked situation than had existed before. Several alternative approaches "consistent with the objective"[24] of removing market distortions "while at the same time causing less interference"[25] exist, other than imposing the concept of blanket communications data on all Member States and citizens.

Impact on law enforcement

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven superfluous for the detection, investigation and prosecution of serious crime.

The Commission tries to justify blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention by claiming it necessary for prosecuting serious crime. As evidence for this claim the Commission cites statistics and examples provided by Member States concerning access to and subsequent use of retained communications data for purposes such as convictions for criminal offences and acquittals of innocent suspects. Without data retention, the Commission claims, such results "might" [sic!] not have been achieved.

First of all, law enforcement interests cannot justify the Directive because its purpose is not facilitating law enforcement. According to the settled case-law of the EU Court of Justice, the interference with fundamental rights an EU measure ensues needs to be justified by the "objectives pursued by the measure chosen".[26] The predominant objective of the Data Retention Directive is ensuring the functioning of the internal market (Articles 114 and 26 TFEU).[27] The EU has no competence in the area of law enforcement, except where specifically police co-operation, judicial co-operation or the approximation of criminal law is concerned, which is not the case with data retention.[28] If the EU relies on internal market objectives for establishing its competence, it cannot rely on a completely different purpose (facilitating law enforcement) for establishing conformity with fundamental rights. If the proper functioning of the internal market is the "predominant" purpose of the Directive, the interference with fundamental rights that comes with it cannot be "predominantly" justified with a completely different purpose which the EU may not legally pursue on the basis of Article 114 TFEU.

Furthermore, even if law enforcement purposes were to be considered, the Commission has failed to prove the necessity of blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention for that purpose. The methodology the Commission uses is unfit to demonstrate necessity. In order to establish the necessity of blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention "for the purpose of the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime" in a scientifically valid way, three points would need to be assessed:

- In how many cases does the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime lack communications data that are available under a blanket retention scheme?

- To the prosecution of how many serious crimes did such extra communications data ultimately make a positive difference?

- Is any such benefit offset by counter-productive side effects of blanket data retention?

In how many cases does the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime lack communications data in the absence of a blanket retention scheme?

A wealth of communications data is available for law enforcement purposes even where providers are in principle obliged to erase such data upon the termination of each communication (see Article 6 of directive 2002/58/EC). Law enforcement authorities can request providers to preserve communications data that is available while a communication is ongoing (e.g. Internet access). Law enforcement authorities can request access to communications data providers retain for billing purposes (e.g. telephone records). Law enforcement authorities can order providers to preserve data relating to future communications of suspects.

The evidence presented by the Commission to justify blanket retention mostly concerns situations where "useful" communications data was available in Member States that have transposed the Directive. Access statistics and examples of usefulness fail to demonstrate necessity though because it is not shown that the data would have been lacking in the absence of a blanket retention scheme. Most of the evidence presented by the Commission is irrelevant because it fails to identify the reason for which "useful" communications data was retained (i.e. commercial purposes, request by law enforcement authorities or blanket retention requirements), thus failing to demonstrate that the data would have been lacking in the absence of a blanket retention scheme. For example, the communications data used to investigate the Madrid bombings were available in the absence of a blanket retention scheme. Even where law enforcement authorities access data specifically retained in accordance with retention obligations, the same data may have been available in the absence of such obligations. The evaluation report fails to demonstrate that any benefits communications data may have for prosecuting crime depend specifically on blanket retention schemes and cannot likewise be achieved under targeted data preservation schemes. The possible occasional utility of access to communications data by law enforcement agencies does not mean that there was a need to retain such data indiscriminately.

The European Court of Human Rights has consistently held that mere usefulness does not satisfy the test of necessity.[29] In a case concerning the retention of biometric data, the European Court of Human Rights critizised data such as now presented by the Commission: "It is true, as pointed out by the applicants, that the figures do not reveal the extent to which this 'link' with crime scenes resulted in convictions of the persons concerned or the number of convictions that were contingent on the retention of the samples of unconvicted persons. Nor do they demonstrate that the high number of successful matches with crime-scene stains was only made possible through indefinite retention of DNA records of all such persons. […] Yet such matches could have been made even in the absence of the present scheme […]."[30]

In order to examine in how many cases the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime lacks communications data, the situation in countries where no blanket retention requirements are or was in place needs to be analysed, which the Commission fails to do. An evaluation which fails to address countries which have not transposed the allegedly "necessary" Directive is, by definition, inadequate.

An independent study commissioned by the German government found that among a sample set of 1.257 law enforcement requests for traffic data made in 2005, only 4% of requests could not be (fully) served for a lack of retained data.[31] The German Federal Crime Agency (BKA) counted only 381 criminal investigation procedures in which traffic data was lacking in 2005[32] and 880 failed requests in 2010[33] In view of a total of the total of about 6 million criminal investigations per year, no more than 0.01% of criminal investigation procedures were potentially affected by a lack of traffic data.[34]

Similarly a dutch study of 65 case files found that requests for traffic data could "nearly always" be served even in the absence of compulsory data retention.[35] The cases studied were almost all solved or helped using traffic data that was available without compulsory data retention.[36]

It follows that in most cases, sufficient communications data for the investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime is available without blanket retention obligations.

To the prosecution of how many serious crimes did such extra communications data ultimately make a positive difference?

Where otherwise unavailable communications data is accessed by law enforcement authorities under a blanket retention scheme, this data often makes no difference to the outcome of the criminal investigation. Often an investigation will be unsuccessful whether or not communiations data is available. For example, communications data can be without benefit to an investigation where they lead to a public telephone booth, a public Internet café, a public Internet access point, a VPN "anonymizing" service, a prepaid mobile telephone card not correctly registered by the subscriber or a device the user of which at the relevant time cannot be established. On the other hand, many criminal offences are successfully prosecuted in spite of the unavailability of communiations data by using other evidence. The making available of more data to law enforcement agencies does therefore not in itself demonstrate that this extra data was necessary for the prosecution of serious crime. Availability is not necessity.

Law enforcement authorities in states that require the deletion of communications data often present statistics on how many requests for communications data were not served due to a lack of communications data. This evidence is irrelevant because it fails to demonstrate any influence extra data would have had on the outcome of these investigations. Likewise, the number of cases in which retained data is used and which result in criminal prosecutions does not demonstrate that blanket retention ultimately made a difference to the outcome of these cases, i.e. to the prosecution of serious crime.

An independent study commissioned by the German government found that about one third of the suspects in procedures with unsuccessful requests for communications data were still taken to court on the basis of other evidence.[37] Moreover 72% of the investigations with fully successful requests for traffic data did still not result in an indictment.[38] All in all, blanket data retention would have made a difference to only 0.002% of criminal investigations.[39] This number does not change significantly when taking into account that in the absence of a blanket data retention scheme, less requests for data are made in the first place.[40]

Is any such benefit offset by counter-productive side effects of blanket data retention?

It has been shown that blanket retention obligations may make a positive difference to the prosecution of a small fraction of criminal offences. Even so, such obligations cannot be considered necessary for the prosecution of serious crime if benefits in some cases are offset by counter-productive side effects on the prosecution of serious crime in other cases.

The indiscriminate retention of communications data without cause has counter-productive effects on the prosecution of serious crime in that it furthers the use of circumvention techniques and other communication channels (e.g. Internet cafés, public wireless Internet access points, anonymisation services, public telephones, unregistered mobile telephone cards, non-electronic communications channels). According to a representative poll after the implementation of the Directive in Germany, 24.6% of Germans declared that they use or intend to use public Internet cafés, 59.8% said that they use or intend to use an Internet access provider that does not retain communications data without cause, and 46.4% of Germans declared that the use or intend to use Internet anonymization technology.[41]

Such avoidance behaviour can not only render retained data meaningless but also frustrate more targeted investigation techniques that would otherwise have been available for the investigation and prosecution of serious crime. Overall, blanket data retention can thus be counterproductive to criminal investigations, facilitating a few, but rendering many more futile.

Also retained data is mostly used for prosecuting petty crime such as minor fraud or filesharing. By tying up law enforcement resources with the mass prosecution of petty crime, blanket retention can hamper the investigation of truly serious crime (e.g. organized crime).

The data provided by blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention is inconclusive

The alleged values of data retention are based upon the ability to trace certain online activities or communication links to individual users responsible or at least to a geographic location. Therefore the effectiveness is based on some axioms.

- Criminals activities are communicated over centralized providers affected by data retention.

- The actual user is also the subscriber.

- The actual user is in any relation to the actual subscriber.

- The geographic location of the user is the same location as the subscribers.

All off these axioms have been proven wrong.

Classic telecommunication is more and more replaced by internet based communication services. [42]Therefore the legislator extended the law to also include VoIP and email based services. This might work for “dedicated” technologies. Most VoIP technologies do not use a central service for the actual communication. The central service only provides a register of subscribers and their IP-addresses like a telephone book and is sometimes used during connection setup, but not required. The VoIP provider is only required when routing traffic to classic telecommunication services.

There are also lots of people providing their own encrypted “VoIP” email, or text message services. There is no central provider that is able to monitor the calls over these types of networks or even identify if it is a VoIP or some other kind of connection. While a lot of people still use centralized providers for VoIP or email communications people that need to transmit confidential data don’t rely on those systems.

Besides of these solutions, most modern instant messengers, online games and other applications provide proprietary Voice over IP or text message capabilities allowing communication between users[43]. It might be possible to provide monitoring for a few of these proprietary technologies but it is impossible to monitor every new communication technology. Using non-centralized (peer2peer or private) encrypted technologies makes it impossible to even determine the kind of communication or any other details besides there is an unidentified link between computers. And even to detect this link requires full monitoring of all communication. Criminals could use those technologies to evade being monitored.

Therefore the impact of data retention is mostly on users of centralized VoIP technologies, who are neglecting the security requirement of their communication.

In most cases there is no way to identify the individual user behind a internet connection or a phone. Families, companies, flat-sharing communities, schools, universities, hotes, restaurants, … are often sharing a single internet connection or a telephone between a group of people. As of now there are no ways to distinguish between the individual users without analysing the actual content.

Therefore identifying an individual user is in most cases only possible if an internet access is only used by a single person. And even for those cases the results are not reliable.

A lot of applications and services are requiring internet access and a certain bandwidth all the time. While mobile services have sufficient coverage in densely populated areas they fail to provide the necessary services or bandwidth in rural environments. To allow people to use their online technologies even in regions not fully covered local subscribers share there bandwidth with other users. The availability of internet access is a significant factor for many restaurants, companies or other localities. So they are reluctantly providing internet access to their customers. Maintaining specific access rules, effectively identifying users, restricting access to specific content or maintaining a list of all customers is a very complex, expensive and an impractical task. Most people and companies lack the knowledge to provide effective measures and the operational costs of intensive surveillance exceeds their economical capabilities.

Even if a detailed monitoring and control of internet access would be possible for every person and company sharing internet access, there would be a high potential for misuse by those individuals acting as telecommunications providers. There are many people providing free wireless internet access in order to illegally steal passwords and other information from careless users. To protect from illegal eavesdropping on unsecure connections, many companies and individuals are redirecting internet traffic through secure channels to a trusted network accessing the internet or other services from there. This technology also makes it impossible to trace the individual user.

Criminals most often masquerade their activities by using computers hacked or infected by malware. Therefore if any suspicion arises the suspect would be the subscriber which was unable to protect his own computer. Currently there is no sufficient protection. Especially home computers are most often barely protected .

Forwarding traffic through proxies, anonymizers, virus-infected computers or other distant locations even masquerades the users location. And makes it difficult upto impossible to trace the individual user.

All in all, blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has no statistically significant impact on crime or the investigation of crime

A meaningful assessment of net effectiveness of blanket retention schemes needs to look at whether, in a given country, serious crime as a whole is prosecuted more effectively under a blanket retention scheme than under a targeted investigation scheme. Has the introduction of a blanket retention scheme led to an increase in the number of condemnations, acquittals, the closure or discontinuation of cases, or the prevention of crimes? Did States operating with targeted instruments achieve a similar number of condemnations, acquittals, the closure or discontinuation of cases, and the prevention of crimes as States operating with blanket retention? The evaluation report fails to assess the effectiveness of law enforcement in Member States and non-Member States that do not have a blanket retention scheme in place.

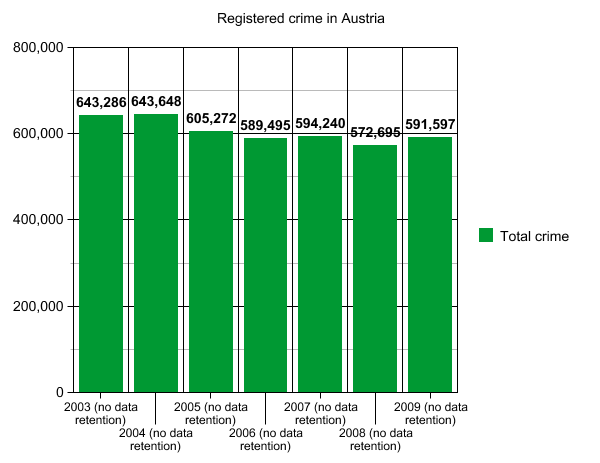

Many law enforcement agencies around the world operate successfully without relying on blanket data retention. Among these states are Austria, Germany, Greece, Norway, Romania, Sweden and Canada. The absence of data retention legislation does not lead to a rise in crime in those states, or to a decrease in crime clearance rates, not even in regard to Internet crime. Nor did the coming into force of data retention legislation have any statistically significant effect on crime or crime clearance.

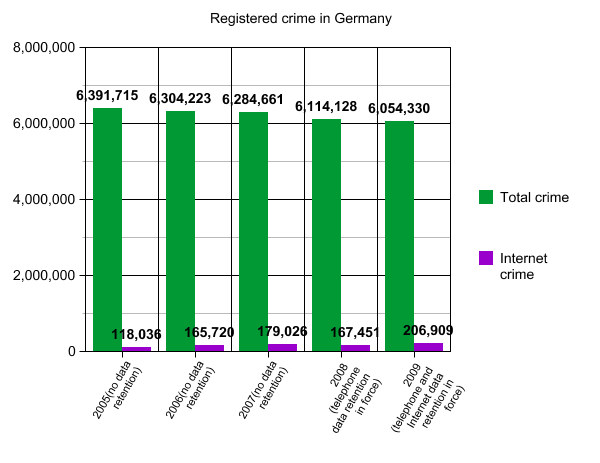

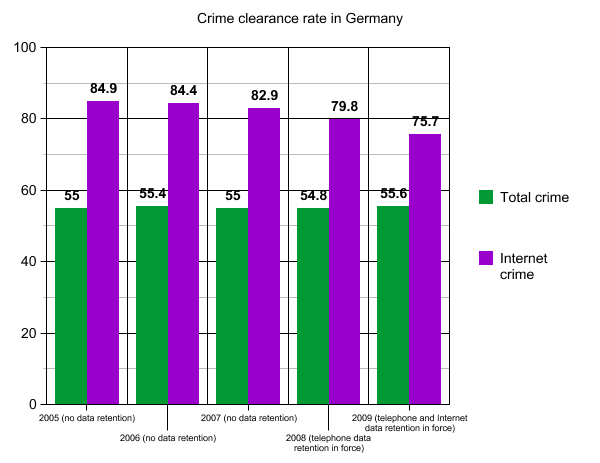

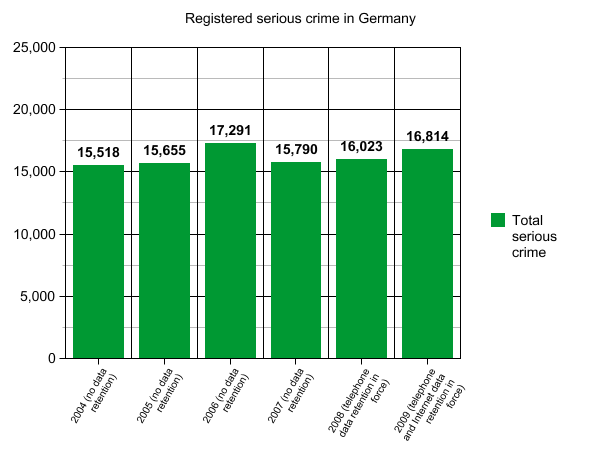

This is exemplified by statistics published by the German Federal Crime Agency (BKA):

With data retention in effect, more serious criminal acts (2009: 16,814) were registered by German police than before (2007: 15,790), and a smaller proportion were cleared up (2009: 83.5%) than before the introduction of blanket retention of communications data (2007: 84.4%). Likewise, after the additional retention of Internet data began in 2009, the number of registered Internet offences surged from 167,451 in 2008 to 206,909 in 2009, while the clear-up rate for Internet crime fell (2008: 79.8%, 2009: 75.7%).[44]

In the absence of a blanket traffic data retention regime, German law enforcement agencies have consistently cleared more than 60% of all reported Internet offences, significantly outperforming the average crime clearance rate of about 50%. The coming into force of data retention legislation did not have any statistically significant effect on crime rates or crime clearance rates. After data retention was discontinued in Germany following the Constitutional Court ruling, the number of detected criminal offences committed on the Internet declined. Internet crime continued to be cleared more often than offline crime even without blanket retention.[45]

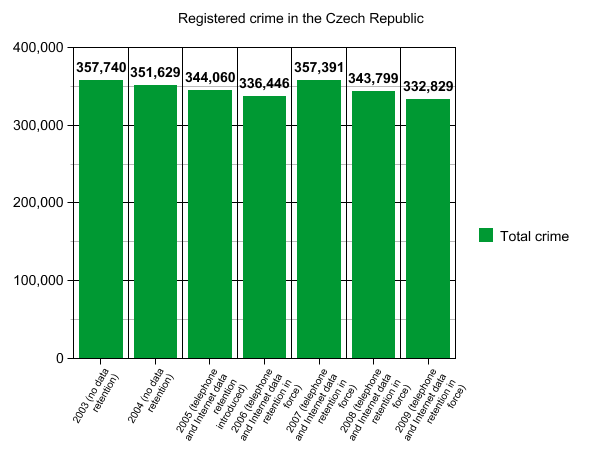

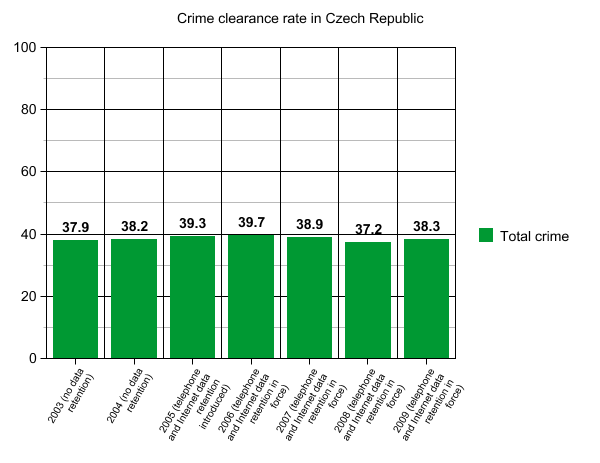

This picture is confirmed by statistics published by the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic and by the Police of the Czech Republic:

Statistics published by the Austrian Ministry of the Interior show that the absence of blanket data retention legislation does not result in a rise in crime or a drop in crime clearance:

For a study titled "The practical effects of data retention on crime clearance rates in EU Member States", the Scientific Services of the German Parliament compared crime clearance rates throughout the EU. The report was finalised on 18 March 2011 and concludes: "In most states crime clearance rates have not changed significantly between 2005 and 2010. Only in Latvia did the crime clearance rate rise significantly in 2007. This is related to a new Criminal Procedure Law though and is not reported to be connected to the transposition of the EU Data Retention Directive."[46]

Notwithstanding the comprehensive evidence presented above, we would like to recall that it is not our task to prove blanket data retention superfluous. It is rather the proponents of this measure who bear the onus of proof regarding the alleged necessity of blanket data retention.

Summary

Facilitating law enforcement is not necessity. Access statistics, anecdotal evidence or perceived utility[47] do not demonstrate a need for blanket data retention. Successful requests for traffic data retained under directive 2006/24 do not prove that data would otherwise have been lacking, despite the commercial billing data stored under directive 2002/58 and extra data stored in compliance with specific judicial orders. Even where extra data is disclosed under data retention schemes, it often has no influence on the outcome of investigation procedures or benefits are offset by avoidance behaviour among citizens. The quota of criminal investigations the outcome of which depends specifically on blanket communications data retention is exceedingly small (about 0.01%) and apparently at least offset by the counter-productive effects that blanket retention has on the prosecution of serious crime.

Studies prove that the communications data available without data retention are generally sufficient for effective criminal investigations. According to crime statistics, serious crime is investigated and prosecuted just as effectively with targeted investigation techniques that do not rely on blanket retention. Blanket data retention has proven to be superfluous in many states across Europe, such as Austria, Belgium (for Internet data), the Czech Republic, Germany, Romania and Sweden. These states prosecute crime just as effectively using targeted instruments, such as the data preservation regime agreed in the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime.

Besides, facilitating the prosecution of crime is not safety. The prevalence of serious crimes is no lower in states or times where communications data are being retained indiscriminately than in other states. There is no proof that telecommunications data retention provides for better protection against crime.

Legality

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention has proven to violate fundamental rights and unable to stand its ground against court challenges.

The Directive claims in recital 22 that it respects the fundamental rights and observes the principles recognised, in particular, by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. However in view of the Directive's at best limited benefits and the widespread harm caused by it, systematically retaining communications data on the entire population cannot be considered a strictly necessary and proportionate measure in a democratic society:

Many democratic states in Europe and beyond prosecute crime effectively without indiscriminate blanket retention. After all, outside telecommunications, crime can be prosecuted without lists of the people's past communications or whereabouts, too. Blanket retention appears to have no statistically significant impact on the crime clearance rate. Enhancing the prosecution of crime is not identical to safety, either. There is no evidence that less crime was being committed in states that have implemented a policy of indiscriminate communications data retention than in other states. In chasing maybe 0.01% of criminal offenders who can be prosecuted on the basis of blanket retention only, the proponents of indiscriminate data retention loose sight of the fact that confidential and untraceable communications protect the lives, health and liberty of far more innocent persons, for example where counselling services can convince violent family fathers or pedophiles to take up therapy. The willingness to discuss negatively regarded activity with counsellors and seek help often depends on the availability of untraceable communications channels. For example, a German helpline could convince a young man to give up plans for a raid on his school in 2007. Had communications data been retained, the student may never have called and may have carried out his plan. At any rate, 98% of all citizens whose communications are being recorded under blanket retention schemes are never even suspected of a criminal offence[48] and use their telephones, mobile phones and the Internet for entirely legal and legitimate purposes.

Even if blanket and indiscriminate retention of communications data of persons never even suspected of an offence did contribute to the detection, investigation and prosecution of serious crime, it fails to strike a fair balance between the competing public and private interests, constituting a disproportionate interference with the EU citizens' right to respect for their private life. Legal experts expect the EU Court of Justice to follow the Constitutional Court of Romania as well as the European Court of Human Rights's Marper judgement and annul the Directive for violating the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

In 2009, the Romanian Constitutional Court ruled that data retention per se breached Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Court argued that the "continuous limitation of privacy" that comes with blanket communications data retention "makes the essence of the right disappear." Data retention "equally addresses all the law subjects, regardless of whether they have committed penal crimes or not or whether they are the subject of a penal investigation or not, which is likely to overturn the presumption of innocence and to transform a priori all users of electronic communication services or public communication networks into people susceptible of committing terrorism crimes or other serious crimes. Law 298/2008 applies practically to all physical and legal users of electronic communication services or public communication networks, so it cannot be considered to be in agreement with the provisions in the Constitution and the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms regarding the guaranteeing of the rights to private life, secrecy of the correspondence and freedom of expression."[49] Making reference to case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, the Romanian Constitutional Court did not only question the compatibility of blanket retention with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, it definitively ruled that it is incompatible.

In 2010, the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany annulled the German data retention requirements for violating the right to secrecy of telecommunications.[50] The Court considered that blanket retention "constitutes a particularly serious encroachment with an effect broader that anything in the legal system to date." Blanket retention "is capable of creating a diffusely threatening feeling of being watched which can impair a free exercise of fundamental rights in many areas." It is "part of the constitutional identity of the Federal Republic of Germany that the citizens’ enjoyment of freedom may not be totally recorded and registered".

In 2011, the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic annulled the Czech data retention requirements for violating the rule of law as well as the rights to data protection and informational self-determination.[51] In the reasons given for the judgment the Constitutional Court expressed fundamental doubts "whether, having regard to the intensity of the interference and the myriad of private sector users of electronic communications, blanket retention of traffic and location data of almost all electronic communications is necessary and appropriate". Referring to crime statistics, the Court pointed out that "blanket retention of traffic and location data had little effect on reducing the number of committed serious crimes".

There are further complaints pending before the Hungarian Constitutional Court[52] and before the Irish High Court. In 2010, the Irish High Court ruled in favour of a request to challenge the Data Retention Directive at the EU Court of Justice.[53] The Court found that data retention had the potential to be of "importance to the whole nature of our society". "[I]t is clear that where surveillance is undertaken it must be justified and generally should be targeted". The Court ruled that civil liberties campaign group Digital Rights Ireland had the right to contest "whether the impugned provisions violate citizen's rights to privacy and communications" under the EU treaties, the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The reference to the EU Court of Justice is expected to be made within the next few months.

The EU Court of Justice can be expected to annul directive 2006/24, having regard to the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. The Grand Chamber of the latter Court found in 2008 that the retention of biometrics on mere suspects breached Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights: "In conclusion, the Court finds that the blanket and indiscriminate nature of the powers of retention of the fingerprints, cellular samples and DNA profiles of persons suspected but not convicted of offences, as applied in the case of the present applicants, fails to strike a fair balance between the competing public and private interests and that the respondent State has overstepped any acceptable margin of appreciation in this regard. Accordingly, the retention at issue constitutes a disproportionate interference with the applicants' right to respect for private life and cannot be regarded as necessary in a democratic society. This conclusion obviates the need for the Court to consider the applicants' criticism regarding the adequacy of certain particular safeguards, such as too broad an access to the personal data concerned and insufficient protection against the misuse or abuse of such data."[54] This assessment of the collection of identification data on 5 million citizens[55] must, a fortiori, apply to the much larger collection of information on the daily communications of 500 million citizens throughout the EU. The Court's finding did not rely on retention periods, but on the fact that personal data of persons not convicted of offences were being retained indiscriminately, as is the case with Directive 2006/24.

Furthermore, the EU Court of Justice will consider that the purpose of the Directive is fundamentally different from the purpose of national data retention laws that have so far been scrutinized by courts. It is settled case-law that the principle of proportionality, which is one of the general principles of European Union law, requires that measures implemented by acts of the European Union are appropriate for attaining the objective pursued by the EU act.[56] While national data retention laws have the objective of facilitating the prosecution of crime, the Directive has the "objective of safeguarding the proper functioning of the internal market".[57] It is in the name of the internal market that the Directive requires even those Member States to implement blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention whose governments, parliaments or constitutional courts do not consider such measure necessary and proportionate for the detection, investigation and prosecution of crime. Insofar as the Directive obliges all Member States to enact blanket retention laws in the name of market harmonisation, the EU cannot primarily rely on the entirely different objective of facilitating law enforcement, which it may not legally pursue under the Directive's legal basis (Article 114 TFEU), for justification.

It is clearly disproportionate for the EU to require all Member States to have confidential communications data retained without cause, merely to prevent competitive (dis)advantages that might exist in a "patchwork" situation where some Member States require providers to retain data and others require deletion. Such a far-reaching interference with the rights protected by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights cannot legitimately be justified and considered proportionate on the basis of justifications and objectives which are essentially economic (removing barriers to the internal market and distortion of competition). The interest in the better functioning of the internal market cannot be considered of such importance that it balances or even outweighs the negative consequences of the unsurpassed interference in privacy caused by the Directive.

In 2010, the EU Court of Justice annulled EU legislation requiring blanket processing of personal data (publication on the Internet) for disproportionately interfering with the fundamental right to privacy, arguing that alternative, targeted measures were available “which would be consistent with the objective of such publication while at the same time causing less interference with those beneficiaries’ right to respect for their private life”.[58] It has been shown that in the case of Directive 2006/24/EC, measures other than imposing blanket retention on all Member States are available which would be consistent with the Directive's objective of safeguarding the proper functioning of the internal market while at the same time causing incomparably less interference with the citizen's right to respect for their private life.

Recommendation

Blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention must be abandoned in favour of a system of expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data.

Considering legal developments since 2005, the scale of the damage done to fundamental rights by the Directive and the unproven effectiveness of data retention for prosecuting serious crime, we urge the Commission to propose outlawing blanket data retention throughout the EU in favour of a system of expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data as agreed in the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime, thus targeting supects of serious crime instead of surveilling 500 million Europeans without cause. According to the EU Court of Justice, the EU is competent to harmonise whether or not telecommunications providers are required to retain communications data for law enforcement purposes. The EU therefore has the power to harmonise the internal market by outlawing national blanket retention requirements, as has been done with tobacco advertising, for example.

According to its evaluation report, the Commission intends to pursue the aim of harmonization by placing law-abiding citizens under general suspicion thoughout the EU. This approach has not only failed by its own standards but costs billions of euros, puts the privacy of innocent people at risk, disrupts confidential communications and paves the way for an ever-increasing mass accumulation of information about the entire population. The EU must look beyond re-using the existing failed approach. Conclusions must be drawn from the experiences of countries that have not implemented the Directive.

We believe that such invasive surveillance of the entire population as comes with blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention is unacceptable. Representatives of the citizens, the media, professionals and industry collectively reject this policy. The EU therefore needs to abandon the failed data retention experiment and embrace targeted, fundamental rights-compliant investigation methods.

At any rate, for as long as the EU Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights have not ruled on pending complaints against data retention legislation, the Commission must not fine or threaten to fine Member States that refuse to (re)enact such legislation.

Draft press release

Show why the Commission fails to demonstrate effectiveness and proportionality, and present our own proposal.

despite lack of evidence of necessity Commission believes that more of the same is needed.

Impact assessment requirements

We believe that the Commission's Impact Assessment for the review of the 2006/24 Data Retention Directive should address the points set out below. Where it is impossible to address a point for lack of data, this should be made transparent in the impact assessment.

Options to be assessed

- Replacing the Directive with a European system of trans-border expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data;

- Outlawing national blanket data retention requirements throughout the EU;

- A combination of options 1 and 2;

- Setting upper limits on national blanket retention requirements only, thus allowing Member States to opt against blanket retention and instead stick with directive 2002/58 and the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime;

- Making full reimbursement of investment and operating cost including personnel compulsory;

- A combination of options 4 and 5;

- Requiring Member States without (optional) national retention legislation in place to impose a levy on their communications service providers, thus eliminating any competitive advantage they might have as a result of not having to retain data indiscriminately;

- Deleting article 15 of directive 2002/58 in order to prohibit Member States from requiring data retention for service providers, types of data or purposes other than those covered by the Directive;

- Limiting the maximum retention period that Member States can impose to 3 months;

- Excluding Internet access, Internet e-mail, Internet telephony and location data from the Directive and include only telephony call records;

- Requiring decentralised data storage and prohibiting direct government access;

- Exempting contacts which particularly rely on confidentiality (e.g. professional communications of and with physicians, lawyers, workers councils, psychologists, helplines, etc.) from storage requirements.

Impact on citizens

The various options should be assessed with regard to their harmful side effects on citizens:

- risk of telecommunications data losses;

- risk of telecommunications data abuse;

- risk of innocent citizens being erroneously subjected to investigation or prosecution, for example due to transposed digits, mismatching time zones or offering public access points;

- risk of deterring citizens from making confidential communications via electronic communication networks and thus impairing the free exercise of fundamental rights:

- impact on psychotherapist or drug abuse counselling, legal advice, crisis line operators and citizens in need of anonymous counselling;

- impact on journalism;

- impact on confidential business communications;

- impact on political activism.

Impact on the internal market

The various options should be assessed with regard to their impact on the internal market for electronic communications:

- Is the option fit to eliminate "appreciable distortions of competition"[59]? In particular, do diverging national data retention requirements or the absence of such result in "appreciable distortions of competition" or do they have "no significant impact" on competition and investment? Based on the current situation, is there a measurable and significant damage to the single market as a result of some countries opting out of the Directive? Any distorsion of competition should be quantified.

- Is the option fit to eliminate distortions of competition better than the current directive does? For example, would a blanket data retention period of 0 to 3 months eliminate any distortions of competition better than the current retention period of 6-24 months?

Impact on the prosecution of serious crime

In order to assess the impact of the various options on the prosecution of serious crime in a scientifically valid way, the following points would need to be addressed:

- In how many cases does the detection, investigation or prosecution of serious crime in the absence of blanket retention legislation lack communications data that would be available under a blanket retention scheme (quantify as a percentage of all serious crime being investigated or prosecuted)?

- To the prosecution of how many serious crimes does such extra communications data ultimately make a positive difference (quantify as a percentage of all serious crime being prosecuted)?

- Is any such benefit offset by counter-productive side effects of blanket data retention (e.g. tying up law enforcement resources with the mass prosecution of petty crime, furthering the use of circumvention techniques and other communication channels)?

- All in all, does the presence or absence of blanket telecommunications data retention legislation in practise have a demonstrable, statistically significant impact on the prevalence or the investigation of serious crime? If so, by how many percent does it increase or decrease the prevalence, the clearance or the prosecution of serious crime? Has the introduction or the absence of blanket telecommunications data retention legislation in the past made a significant difference to the number of condemnations, acquittals or the closure or discontinuation of serious crime cases in a given state? If so, by how many percent did the number of condemnations, acquittals or the closure or discontinuation of serious crime cases increase or decrease as a result of blanket telecommunications data retention legislation or its absence?

Impact on public opinion

The various options should be assessed with regard to their impact on public opinion (e.g. by way of a Eurobarometer poll). For example, is there acceptance of blanket and indiscriminate telecommunications data retention? Is there acceptance of an EU-wide blanket and indiscriminate communications data retention requirement or should this decision be taken by national parliaments and constitutional courts? Is there acceptance of a trans-border expedited preservation and targeted collection of traffic data instrument?

References

- ↑ CEPOS, Logningsbekendtgørelsen bør suspenderes med hendblik på retsikkershedsmæssig revidering, p. 4, 20 July 2010, based on official figures for 2008 from the Danish Ministry of Justice, http://www.cepos.dk/publikationer/analyser-notater/analysesingle/artikel/afvikling-af-efterloen-og-forhoejelse-af- folkepensionsalder-til-67-aar-vil-oege-beskaeftigelsen-med-1370/

- ↑ MIT, http://reality.media.mit.edu/dyads.php, http://reality.media.mit.edu/user.php and http://reality.media.mit.edu/eigenbehaviors.php.

- ↑ http://www.edps.europa.eu/EDPSWEB/webdav/site/mySite/shared/Documents/EDPS/Publications/Speeches/2010/10-12-03_Data_retention_speech_PH_EN.pdf

- ↑ Infas poll, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/infas-umfrage.pdf.

- ↑ Flash Eurobarometer, Data Protection in the European Union, February 2008,http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_225_en.pdf, p. 48 (32+18+19=69%, 35+21+25=81%).

- ↑ Recital 25 notes that "Issues of access to data retained pursuant to this Directive [...] fall outside the scope of Community law."

- ↑ Forsa, Opinions of citizens on data retention, 2 June 2008, http://www.eco.de/dokumente/20080602_Forsa_VDS_Umfrage.pdf or http://www.webcitation.org/5sLeT8Goj.

- ↑ Antworten auf den Fragebogen der Europäischen Kommission vom 30.09.2009 zur Vorratsdatenspeicherung, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/antworten_kommission_vds_2009-11-13.pdf, p. 2.

- ↑ http://www.tjmcintyre.com/2011/02/judges-report-reveals-allegations-that.html

- ↑ http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.berlinonline.de%2Fberliner-zeitung%2Farchiv%2F.bin%2Fdump.fcgi%2F2007%2F0831%2Fpolitik%2F0062%2Findex.html&date=2011-03-26

- ↑ Meyen/Springer/Pfaff-Rüdiger, Free Journalists in Germany, 20 May 2008, http://www.dfjv.de/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/DFJV_Studie_Freie_Journalisten.pdf or http://www.webcitation.org/5sLdXIt55, p. 22.

- ↑ http://wiki.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/Heft_-_es_gibt_keine_sicheren_daten_en.pdf

- ↑ http://wiki.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/Heft_-_es_gibt_keine_sicheren_daten_en.pdf

- ↑ http://wiki.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/Heft_-_es_gibt_keine_sicheren_daten_en.pdf

- ↑ ECJ, C‑301/06, § 68.

- ↑ Advocate General, C-301/06, § 85.

- ↑ Legislation with a view to imposing data retention obligations had been enacted in Belgium, France, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the Czech Republic.

- ↑ Commission, SEC(2005)1131.

- ↑ Legislation transposing the directive is not in effect in Austria, Belgium (concerning Internet data), the Czech Republic, Germany, Romania and Sweden. Based on recent Constitutional Court decisions, blanket retention is likely to be discontinued in other Member States where it is challenged in Constitutional Courts.

- ↑ For example, the UK does not require small operators to retain data, arguing that "the costs outweigh the benefits".

- ↑ SEK(2005)438

- ↑ ECJ, C-376/98, § 106; C-58/08, § 32.

- ↑ The German Federal Constitutional Court has held that the government may, in principle, not confer criminal procedure or military competences on the EU except for cross-border issues. BVerfG, 2 BvE 2/08, § 253.

- ↑ ECJ, C-92/09, § 81.

- ↑ ECJ, C-92/09, § 81.

- ↑ ECJ, C-58/08, § 53; C-92/09, § 74.

- ↑ ECJ, C‑301/06, §§ 72 and 85.

- ↑ Advocate General, C-301/06, §§ 99 and 100.

- ↑ Silver v. UK (1983) 5 EHRR 347, § 97.

- ↑ ECtHR, Marper v United Kingdom (2009) 48 EHRR 50, § 116.

- ↑ Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law, The Right of Discovery Concerning Telecommunication Traffic Data According to §§ 100g, 100h of the German Code of Criminal Procedure, March 2008, http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/16/084/1608434.pdf, p. 150.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/schriftsatz_2008-03-17.pdf, p. 2.

- ↑ Report of 17 September 2010, p. 6.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/schriftsatz_2008-03-17.pdf, p. 2.

- ↑ Erasmus University Rotterdam, Who retains something has something, 2005, http://www.erfgoedinspectie.nl/uploads/publications/Wie%20wat%20bewaart.pdf, p. 43.

- ↑ Erasmus University Rotterdam, Who retains something has something, 2005, http://www.erfgoedinspectie.nl/uploads/publications/Wie%20wat%20bewaart.pdf, p. 28.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Starostik, Pleadings of 17 March 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ infas institute poll, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/infas-umfrage.pdf.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Arbeitskreis Vorratsdatenspeicherung analysis, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/data_retention_effectiveness_report_2011-01-26.pdf.

- ↑ http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/content/view/435/79/lang,en/.

- ↑ Scientific Services of the German Parliament, Report WD 7 – 3000 – 036/11, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/Sachstand_036-11.docx.

- ↑ Such as cited in the “Overview of information management in the area of freedom, security and justice”, COM(2010)385, p. 36, as well as in a “Room Document”, http://www.vorratsdatenspeicherung.de/images/RoomDocumentEvaluationDirective200624EC.pdf.

- ↑ In 2009, 1'724'839 of 81'866'000 inhabitants were suspected of a criminal offence: Federal Crime Agency, http://www.bka.de/pks/pks2009/download/pks-jb_2009_bka.pdf, p. 73.

- ↑ Constitutional Court of Romania, decision of 8 October 2009, http://www.legi-internet.ro/english/jurisprudenta-it-romania/decizii-it/romanian-constitutional-court-decision-regarding-data-retention.html.

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, decision of 2 March 2010, http://www.bverfg.de/en/press/bvg10-011en.html.

- ↑ Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, decision of 31 March 2011, http://www.concourt.cz/clanek/GetFile?id=5075.

- ↑ Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, Constitutional Complaint Filed by HCLU Against Hungarian Telecom Data Retention Regulations, 2 June 2008, http://tasz.hu/en/data-protection/constitutional-complaint-filed-hclu-against-hungarian-telecom-data-retention-regulat.

- ↑ High Court of Ireland, decision of 5 May 2010, http://www.scribd.com/doc/30950035/Data-Retention-Challenge-Judgment-re-Preliminary-Reference-Standing-Security-for-Costs.

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights, decision of 4 December 2008, http://www.webcitation.org/5g6FzdBr4, § 125.

- ↑ Human Genetics Commission, Nothing to hide, nothing to Fear?, November 2009, http://www.hgc.gov.uk/UploadDocs/DocPub/Document/Nothing%20to%20hide,%20nothing%20to%20fear%20-%20online%20version.pdf, p. 4.

- ↑ ECJ, C-92/09, § 74.

- ↑ ECJ, C-301/06, §§ 72 and 85.

- ↑ ECJ, C‑92/09 and C‑93/09, § 81.

- ↑ ECJ, C-376/98, § 106; C-58/08, § 32.